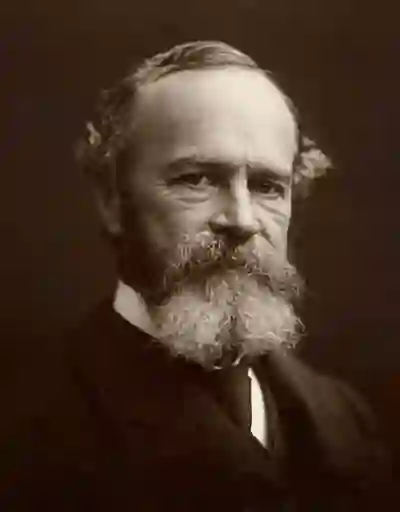

Who Is William James

William James (1842–1910) was an American philosopher and psychologist widely regarded as the father of American psychology and one of the most important thinkers in the pragmatist tradition. Trained as a physician at Harvard, he never practiced medicine but instead built one of the first psychology laboratories in the United States and spent decades teaching philosophy and psychology at Harvard. His intellectual range was extraordinary—spanning physiology, psychology, philosophy of mind, religion, and ethics—and he brought to all of it a deep respect for the messiness and variety of actual human experience.

What makes James permanently relevant to IMHU's mission is his insistence, radical for his era and still underappreciated in ours, that mystical and religious experiences deserve rigorous study on their own terms. Rather than explaining them away as pathology or reducing them to neurological side-effects, he treated them as data—important data about what the human mind can do and what it might mean. His 1902 masterwork The Varieties of Religious Experience remains one of the most cited books in the psychology of religion and set a precedent that researchers like Andrew Newberg, David Yaden, and Ann Taves continue to build on today.

Core Concepts

- Radical empiricism and the primacy of experience: James argued that philosophy and psychology should start with experience as it is actually lived—not with abstract theories about what experience ought to be. This meant taking seriously the full range of human states, including ecstatic, mystical, and anomalous ones. For anyone working at the intersection of mental health and spirituality, this is foundational: it gives you philosophical permission to treat a client's spiritual experience as real and meaningful before reaching for a diagnostic label.

- The four marks of mystical experience: In Varieties, James proposed that mystical states share four common features: ineffability (they resist adequate description), noetic quality (they feel like revelations of deep truth), transiency (they don't last long), and passivity (the person feels "grasped" by something beyond their will). These markers remain the starting framework for nearly every subsequent attempt to define and study mystical experience. They're useful clinically, too—they help distinguish transformative spiritual experiences from psychotic episodes, which typically lack the noetic quality and the sense of coherent meaning.

- The "sick soul" and the "healthy-minded": James mapped two broad temperaments in religious life: the "healthy-minded," who naturally gravitate toward optimism and see the divine in life's goodness, and the "sick soul," who must pass through suffering, doubt, and existential darkness before arriving at faith. He didn't pathologize either type—both were legitimate paths. This framework anticipates much of what we now discuss as spiritual emergency, dark nights of the soul, and post-traumatic growth. It's a reminder that transformation doesn't always look tidy.

- Pragmatism — truth is what works: James's pragmatism holds that the value of a belief lies in its practical consequences for living. Applied to spirituality: rather than asking "Is this experience objectively real?" the pragmatic question is "What difference does this experience make in how someone lives?" This reframing is immensely useful for clinicians who need to support clients' spiritual lives without getting stuck in metaphysical debates.

- The stream of consciousness: James introduced the metaphor of consciousness as a continuous, flowing stream rather than a chain of discrete mental events. This concept influenced not only psychology and neuroscience but also literature (Virginia Woolf, James Joyce) and contemplative practice. It aligns well with mindfulness traditions that emphasize observing the flow of experience without grasping.

Essential Writings

- The Varieties of Religious Experience (1902): The essential text. Based on his Gifford Lectures in Edinburgh, James surveys conversion experiences, saintliness, mysticism, and the psychology of religion with extraordinary breadth and empathy. Best use: the single best starting point for anyone who wants to understand why spiritual experiences matter psychologically—and why dismissing them is bad science.

- The Principles of Psychology (1890): A massive, brilliant textbook that established psychology as a legitimate science in America. It introduced concepts like the stream of consciousness, habit formation, and the James-Lange theory of emotion. Best use: foundational reading for understanding how James thought about the mind—dense but endlessly rewarding.

- Pragmatism (1907): A series of lectures laying out his philosophical method: judge ideas by their practical consequences, not their abstract elegance. Best use: a philosophical toolkit for anyone navigating the tension between scientific materialism and spiritual openness—James shows you don't have to choose.

- The Will to Believe (1897): James's argument that in matters where evidence is genuinely inconclusive—like the existence of God or the meaning of mystical experience—it can be rational to let your will tip the balance toward belief, especially if believing leads to a better life. Best use: a powerful essay for anyone wrestling with whether it's intellectually honest to take spiritual experience seriously.