Who Is Rabia al-Adawiyya

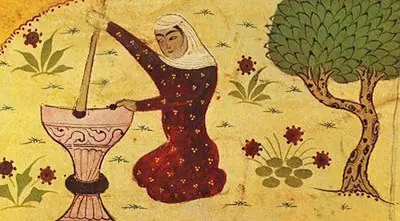

Rabia al-Adawiyya (c. 717–801 CE), also known as Rabia of Basra, was an early Muslim saint and mystic who is widely regarded as one of the foundational figures of Sufism and the most celebrated woman in the history of Islamic spirituality. Born into poverty in Basra (in present-day Iraq), orphaned young, and sold into slavery, Rabia was eventually freed—tradition holds that her master witnessed her praying in a state of luminous ecstasy and recognized her spiritual stature. She spent the remainder of her life in Basra as an ascetic and teacher, attracting a circle of followers that included some of the most prominent early Sufis, including Hasan al-Basri (though the historical accuracy of their interactions is debated).

Rabia’s transformative contribution to Islamic mysticism was the introduction of selfless, unconditional love (mahabba) as the central axis of the spiritual life—a radical shift from the earlier Sufi emphasis on asceticism, fear of God, and hope for paradise. Her famous prayer—asking God to burn her in hell if she worships from fear, and exclude her from paradise if she worships from hope, so that only pure love remains—became one of the most quoted passages in Sufi literature and established a new paradigm for the mystic’s relationship with the divine. She rejected multiple offers of marriage, declaring that her love for God left no room for human attachment. Though she left no written works, her sayings, prayers, and stories were preserved by later writers (most notably the twelfth-century hagiographer Farid al-Din Attar in his Memorial of the Saints) and have influenced Sufi poetry, theology, and practice for over a millennium. She remains a powerful symbol of women’s spiritual authority in Islam and of the primacy of love over law in the mystical tradition.

Core Concepts

- Divine love (mahabba) as the supreme spiritual motive

- Rabia’s most revolutionary contribution was establishing selfless love of God—rather than fear of punishment or desire for reward—as the highest and purest form of worship. This was a genuine paradigm shift in early Islamic spirituality: before Rabia, the dominant modes were ascetic renunciation and eschatological fear. Her teaching that authentic devotion must be purified of all self-interest—including the desire for paradise—set the agenda for the great love-mystics who followed, from Hallaj to Rumi to Ibn ʿArabi. (Wikipedia)

- The purification of intention

- Rabia’s teaching extends beyond emotion into a rigorous psychology of intention: every act of worship must be examined for hidden self-interest. Even devotion motivated by hope of paradise is, in her framework, a form of spiritual commerce. This radical standard of sincerity (ikhlas) became central to later Sufi ethics and anticipates modern psychological insights about the role of unconscious motivation in ostensibly altruistic behavior.

- Renunciation as the ground of freedom

- Rabia lived in extreme material simplicity—refusing marriage, wealth, and patronage—not as self-punishment but as the necessary clearing of space for undivided attention to God. Her asceticism was instrumental, not an end in itself: by removing worldly attachments, the heart becomes available for the one relationship that matters. This positions her within the broader cross-cultural pattern of contemplative renunciation found in Buddhist, Hindu, and Christian traditions.

- Women’s spiritual authority in Islam

- Rabia’s prominence as a teacher, her rejection of subordination to male authority in matters of the spirit, and her acceptance by male Sufis as a spiritual superior make her a crucial figure for understanding women’s roles in Islamic mysticism. While her historical reality is filtered through hagiographic layers, the tradition’s consistent honoring of her authority demonstrates that Sufism has, at least in principle, recognized spiritual realization as transcending gender.

Essential Writings

- Rābiʿa: From Narrative to Myth (Rkia Elaroui Cornell)

- The most rigorous modern scholarly study of Rabia: Cornell carefully separates the historical evidence from the layers of hagiographic elaboration, reconstructing what can actually be known about the historical Rabia while analyzing how her story was shaped by later writers to serve different theological agendas.

- Best use: for readers who want to understand the real Rabia behind the legend—and why the distinction matters.

- Muslim Saints and Mystics: Episodes from the Tadhkirat al-Auliya (Memorial of the Saints) (Farid al-Din Attar, trans. A.J. Arberry)

- Attar’s twelfth-century hagiography is the primary source for most of the stories and sayings attributed to Rabia. His account is devotional rather than historical, but it preserves the teachings and parables that have shaped how the Sufi tradition remembers her.

- Best use: the traditional source—read the Rabia chapter for the stories, prayers, and sayings that have resonated across a thousand years of Sufi practice.

- Doorkeeper of the Heart: Versions of Rabia (Charles Upton)

- A collection of lyrical English renderings of Rabia’s prayers and sayings, presented as contemplative poetry. Upton works from multiple sources to create versions that capture the spiritual intensity of Rabia’s voice.

- Best use: a devotional and contemplative companion—short, beautiful, and suitable for daily reflective reading.