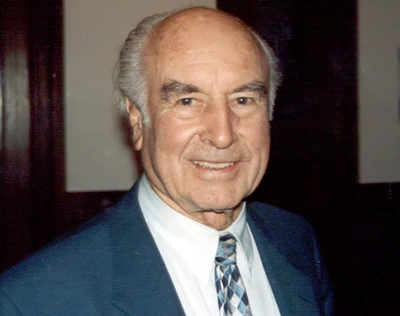

Who Is Albert Hofmann

Albert Hofmann (1906–2008) was a Swiss chemist who, while working at Sandoz Laboratories in Basel, first synthesized lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD-25) in 1938 and accidentally discovered its extraordinary psychoactive properties in 1943 during what has become known as "Bicycle Day"—his famous ride home after inadvertently absorbing a dose through his fingertips. That accidental discovery launched one of the most consequential and controversial chapters in the history of psychiatry, neuroscience, and Western spirituality.

Hofmann was not a counterculture figure. He was a meticulous, conservative scientist who spent his career at a major pharmaceutical company and was deeply troubled by the recreational use and subsequent prohibition of the substance he had created. He viewed LSD as a tool of extraordinary potential for psychiatry, consciousness research, and spiritual development—but one that demanded careful set, setting, and professional guidance. His lifelong advocacy for responsible psychedelic research, combined with his personal conviction that LSD had shown him something genuinely true about the nature of consciousness and reality, makes him a foundational figure for anyone interested in the intersection of psychedelics, mental health, and spirituality.

Core Concepts

- LSD as a "problem child": Hofmann famously called LSD his "problem child"—a discovery of immense promise that had been misused, misunderstood, and ultimately criminalized. He argued that the substance's potential for therapeutic and spiritual benefit was real and well-documented, but that irresponsible use and political backlash had prevented it from being properly integrated into medicine and culture. This framing—acknowledging both the power and the danger—remains the most intellectually honest position in psychedelic discourse.

- The continuity between psychedelic and mystical experience: Hofmann was convinced, based on his own experiences and decades of observing clinical research, that LSD could catalyze genuine mystical states indistinguishable from those described in the world's contemplative traditions. He didn't see this as reducing mysticism to chemistry; rather, he saw the chemical as a key that opened a door already present in human consciousness. This position aligns with the "perennial" view and has been supported by subsequent research from Johns Hopkins and Imperial College London.

- Sacred chemistry in nature: Hofmann's later research focused on psilocybin (from Psilocybe mushrooms) and the morning glory seeds used in Mazatec shamanic traditions. He was deeply interested in the fact that nature produces psychoactive compounds that interact so precisely with human brain chemistry, and he saw this as evidence of a deeper relationship between consciousness and the natural world—not mere biochemical accident.

- Set, setting, and responsibility: Long before these concepts became standard in psychedelic therapy, Hofmann emphasized that the effects of LSD depend enormously on the mental state of the user (set) and the physical and social environment (setting). He argued that most "bad trips" and adverse outcomes resulted from careless use, not from inherent properties of the substance—a position now well-supported by clinical data.

- The need for a new consciousness: In his later years, Hofmann increasingly framed psychedelics within an ecological and spiritual context, arguing that humanity's destructive relationship with the natural world stemmed from a crisis of consciousness—a failure to perceive the interconnectedness that psychedelic experience can reveal. He saw responsible psychedelic use as one potential tool (among others) for catalyzing the shift in awareness that ecological survival requires.

Essential Writings

- LSD: My Problem Child (1980): Hofmann's memoir and the definitive first-person account of LSD's discovery, early research, cultural explosion, and prohibition. Written with scientific precision and quiet passion, it's both a historical document and a personal testament to the substance's potential. Best use: the essential starting point for anyone interested in the history and philosophy of psychedelic research.

- The Road to Eleusis: Unveiling the Secret of the Mysteries (1978, with R. Gordon Wasson and Carl Ruck): A speculative but fascinating investigation into whether the ancient Greek Eleusinian Mysteries—widely considered the most important religious ritual in the ancient world—involved a psychedelic sacrament derived from ergot (the same fungal source as LSD). Best use: for readers interested in the deep historical roots of psychedelic-spiritual experience.

- Insight/Outlook (1989): A collection of Hofmann's later reflections on consciousness, nature, and the role of psychedelics in human development. More philosophical than LSD: My Problem Child, it reveals the depth of his thinking about the relationship between chemistry, consciousness, and meaning. Best use: for readers who want Hofmann the philosopher, not just Hofmann the chemist.

Image Attribution

“Albert Hofmann.jpg” by MatthiasKabel, via Wikimedia Commons, licensed CC BY-SA 3.0. Link: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3AAlbert_Hofmann_Oct_1993.jpg